When looking at the New York Times’ David Leonhardt’s fascinating research on how your location determines your income mobility, there are some obvious conclusions.

We all know that there are certain areas where poverty is rampant and multi-generational. Those are areas where we would expect income mobility to be low.

What is striking is that even the earning potential of the affluent is affected by location. In areas designated below average in income mobility, future income is also diminished for high income households.

Some will take this data and simply conclude that families must leave low income mobility areas in favor of high income mobility areas. Certainly, we have seen instances where that has already taken place.

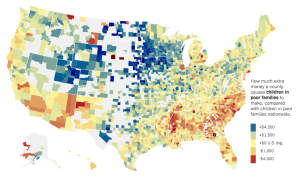

However, what if low income mobility areas greatly outnumber high income mobility areas? There are certain regions of the U.S. where some combination of family traditions, marketable skill sets, and quality of life concerns limit where you are willing to move. A look at the U.S. map shows there are very few states that are effectively avoiding this problem.

Areas in blue and green indicate good income mobility, while red and orange areas suggest improvement is necessary. Though it appears that the Great Plains region is excelling, the South and Southwest regions are not.

Therefore, what can be done to boost income mobility, so that overall living standards improve?

First, let us look at five common themes that drive good income mobility:

- Less segregation by income and race

- Lower levels of income inequality

- Better schools

- Lower rates of violent crime

- Larger share of two-parent households

Perceived cultural differences drive residential segregation patterns. When there is the presence of unruly children and lack parental involvement in the schools of some communities, upwardly mobile parents are reluctant to place their children in those schools.

This mindset has implications that drive all five of the above factors. White flight emerges and drives them away from blacks because there is a perception that black families have discipline issues and devalue education. High income families isolate themselves from low income families for similar reasons.

Regions where there are one or two good schools surrounded by a number of under-performing schools can stigmatize a region and reduce overall investment and job creation. Those economic factors often drive up violent crime and result in more unfavorable family compositions.

In order to address this problem, we must realize that solutions must come locally, rather than nationally. In an era of high federal deficits and strained state budgets, it will be difficult to solve these socioeconomic problems with an influx of public funding.

Instead, it will take strong and inclusive civic leadership where serious dialogue takes place on race and social class. Identifying influential leaders covering a broad spectrum of the community, including industry, education, non-profit organizations, and religious institutions, will be essential. Establishing parameters that allow for free-flowing dialogue will be challenging, but necessary to overcome the wall of fear and mistrust.

Communities committed to active engagement and willingness to seek common ground on difficult issues will thrive. On the other hand, communities accepting the status quo will continue to wilt.

Are you willing to start the dialogue and push your community forward?